Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start writing!

Author: admin

-

Science | Class 11th Notes | Physics | Unit – 1 Physical World and Measurements Chapter – 2 Systems of Units (Part – I)

We provide students with the best science notes for class 11th that helps to repack the long and lengthy course into a short series of easy notes that reduces the burden from the shoulders of students regarding heavy course and hard study and shows them a new and easy way to study. Until class 10th, students were taught in a lengthy, easy and explained method so that their basic knowledge about science gets strong. Class 11th is about expanding that basic knowledge and have got a very lengthy course which is many times more than that of 9th and 10th class. Also, if a student seeks to go into competitions like I.I.T., A.I.E.E.E., A.I.M.M.S. than the load of study he needs to do is much more increased. This load can be decreased if he is presented his vast course in form of short and easy notes which the students can easily understand and learn. That is why we have prepared the whole large and vast course for Class 11th in form of short and easy notes for our students. You can read them and find it out for yourself how easy is to read and learn them. We would appreciate your feedbacks or suggestions in form of comments and if there is something still missing, we will be keeping updating the post for you. You must keep visiting the website to get those updates.

In the second chapter of first unit, we come across a problem. A large number of topics is to be covered in the second chapter, each topic having specific type of questions, problems and numericals associated with them. Fitting all those topics in one chapter would make it difficult to understand and the chapter will become really bulky. So, we have divided the second chapter into four parts, ‘Units and quantities’, ‘Length, mass and time measurement’, ‘Dimensional Analysis’ and ‘Error Analysis’. This would help the students to understand all the topics in four different parts and making them easier to understand and learn.

Science for class – XI

Unit -1: Physical world and measurements

Although we have been studying the physics from a long time, still there is not everything we have been able to clear out in our previous classes. We need to revisit the world of physics with a new dimension and explore the basics of physics and physical study again so that nothing remains uncovered and no single basic concept of physics is left. In unit Ist i.e. Physical world and measurements, we look at all the basic knowledge of physics so that armed with this knowledge we can move onto further deep study of physics in further units.

Chapter – 2: Systems of Units

Part-1: Units and Quantities

2.1.1 – Introduction

In this first part of chapter two, we will discuss the topics surrounding units and quantities. We would discuss about some earlier definitions of some common units and then introduce the SI system of units and how it defines the basic and supplementary units.

2.1.2 – What are units?

Before we move on to units, let us talk about physical quantities.

Physical quantity: All quantities in terms of which laws of physics can be explained and which can be measured directly or indirectly are physical quantities. For example length, mass, time etc.

Now let us move to units.

Units: The standard that is chosen as reference in order to measure a physical quantity is called the unit of that quantity. For example, the unit of length which is metre, or the unit of mass which is kilogram.

Process of measurement of physical quantities:

- The selection of the unit.

- Determining the number of times the unit is contained in that physical quantity.

For example, in the first step, we select metre as the unit of length. Next, in the second step, we measure the length of a room. To do so, we determine how many metres are contained in the room we are measuring. We know that the room’s length can be measured using various methods and we usually say that the room is 7 metres or 8 metres.

Measure of a physical quantity = Numerical value of the physical quantity × Size of its unit

X = n u

It follows that if the size of the unit is small, numerical value of the quantity will be large and vice-versa.

n u = constant

If n1 = numerical value of physical quantity of unit u1.

n2 = numerical value of physical quantity of unit u2.

n1 u1 = n2 u2

2.1.3 – Fundamental and Derived Units.

As the title says, in this topic we would discuss about two different categories of units.

Fundamental units: Those units which are neither derived from other units, nor can be further resolved into other units are known as fundamental units.

Mass, length and time are fundamental quantities and their units are called fundamental units.

Derived units: Those units which are derived from other fundamental units are known as derived units.

Area is a derived unit. If the side of a square is ‘x’ metres, then its area is x × x = x2 metres.

The unit of any physical quantity can be derived from its defining equation. e.g.:

Speed = Distance/Time

Unit of speed = Unit of length/Unit of time

= metre/second

=m s-1

2.1.4 – Standard Units.

A unit that is most appropriate or most suitable for a quantity/physical quantity is called a standard unit.

Characteristics of a standard unit:

- It should be well-defined.

- It should be of suitable size i.e. neither too large nor too small.

- It should be easily reproducible at all places.

- It should not change with time and from place to place.

- It should not change with change in physical properties.

- It should be easily accessible.

2.1.5 – Some physical units and their earlier definitions

Unit of mass:

Mass: Mass of a body is the quantity of matter it contains.

Mass of a material body can never be zero. The internationally accepted unit of mass is kilogram.

Unit of length:

Length: Length of an object is the distance of separation between its two ends.

Internationally accepted unit of length is metre.

Unit of time:

Time: It is not possible to define time in absolute terms. However, according to Einstein, time is simply what a clock reads.

Internationally accepted unit of time is second.

Earlier definitions of these units:

Mass:

- Originally, one kilogram was defined as the mass of one cubic decimetre of water at 4° (Temperature of water at maximum density)

- The General Conference of Weights and Measures defined one kilogram as the mass of a platinum-iridium cylinder kept at the International Bureau of Weights and Measures at Sevres, near Paris, France.

Length:

- In 1971, the Paris Academy of Sciences defined metre as one-tenth millionth of the distance from north pole to equator.

- In 1899, the General Conference of Weights and Measures defined metre as the distance between two lines marked on a platinum-iridium rod kept at a constant temperature of 273.16 K preserved at International Bureau Of Weights And Measures.

Why was this not a convenient definition of metre?

There are two reasons:

- If the temperature of the rod changes, its length will change too.

- It will be difficult to compare any metre rod or a newly produced rod with the preserved rod.

Time:

- Paris Academy of Sciences defined one second as the time taken by a simple pendulum of one metre to swing between two extreme points.

- The time when sun is at the highest point is called noon. Solar day is the time that elapses between noons of two consecutive days.

Mean solar day is the average of all solar days in one year. And a solar second is the (1/24 × 60 × 60)th of a mean solar day.

Why was this definition not appropriate?

Duration or length of a mean solar day is different for different years. So, this definition was not appropriate.

Q – What difficulties did earlier units of mass and length did present?

Some difficulties were:

- It was difficult to preserve kilogram and a metre bar.

- It was difficult to replicate them for their use in different countries.

- It was difficult to compare the replicas with the preserved kilogram and metre bar.

2.1.6 – International systems of units.

- cgs system :

- French system of units.

- Uses centimetre, gram and second as basic units.

- It is a metric system of units.

2.fps system :

- British/English system of units.

- Uses foot, pound and second as basic units.

- It is not a metric system of units.

3.mks system :

- Also a French system of units.

- Uses metre, kilogram and second as basic units.

- A metric system of units. Closely related to cgs system.

- A coherent system of units.

Coherent system of units: If all derived units can be obtained by either multiplying or dividing its fundamental units, such that no numerical factors are introduced.

4.SI : The General Conference of Weights and Measures held in 1960 introduced a new logical system of units known as Systeme Internationale d’ Unites or SI in short.

- Redefines units on the basis of atomic standards.

- Covers all the branches of physics.

- Based on seven basic and two supplementary units.

Following is the table of the seven basic units defined by SI:

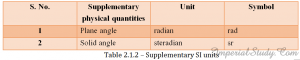

Following is the list of supplementary SI units:

2.1.7 – Basic and supplementary SI units.

Basic units:

Metre: According to General Conference of Weights and Measures, one metre equals to 1,650,763.3 wavelengths in the vacuum of orange-red radiation emitted by Krypton with atomic mass 86.

In 1983, metre was redefined as length of path travelled by light in vacuum during a time interval of 1/299,792,458 of a second.

Kilogram : It was not redefined on atomic standards. So, one kilogram is the mass of the platinum-iridium cylinder kept at the International Bureau of Weights and Measures in Sevres, near Paris, France.

Second : In 1964, the twelfth General Conference of Weights and Measures defined second as equal to the duration of 9,192,631,770 vibrations corresponding to the transition between two hyperfine levels of cesium-133 atom in the ground state.

Kelvin : It is defined as 1/273.16th fraction of the thermodynamic temperature at the triple point of water.

Ampere : One ampere is defined as the current generating a force of 2 ×10-7 newton per metre square between two parallel straight conductors of infinite length and negligible circular cross-section, when placed one metre apart in vacuum.

Candela : One candela is the luminous intensity in the perpendicular direction of a surface of 1/6,00,000 square metre of a black body at a temperature of freezing platinum (2046.65 K) and under a pressure of 1,01,325 newton per metre square.

In 1979, candela was redefined as the luminous intensity in a given direction due to a source which emits monochromatic radiation of frequency of 540 × 1012 Hz and of which the radiant intensity in that direction is 1/683 watt per steradian.

Mol : One mol was defined as the amount of substance having the same number of elementary particles as there are atoms in 0.012 kg of carbon-12.

Supplementary SI units:

Radian : It is the plane angle between two radii of a circle, which cut off from the circumference, an arc equal to the length of the radius of the circle.

plane angle (in radian) = length of arc/radius

Steradian : It is the solid angle with its apex at the centre of a sphere, which cuts out an area on the surface of the sphere equal to the area of an square whose sides are equal to the radius of the circle.

solid angle (in steradian) = area cut out from the surface of the sphere/radius2

2.1.7 – Advantages of SI.

- It is a rational system of units : It makes use of only one unit for one physical quantity while other systems may use different units for a single quantity.

- SI is a coherent system of unites : All derived units can be obtained by dividing and multiplying basic and supplementary units and no numerical factors are introduced, while in other systems, numerical factors may be introduced.

- Closely related to cgs system : It is very easy to convert cgs units into SI units or vice-versa.

- SI is a metric system : Like cgs and mks, SI is also a metric system of units. All multiples and submultiples can be expressed as the powers of 10.

2.1.8 – Some prefixes in power of 10.

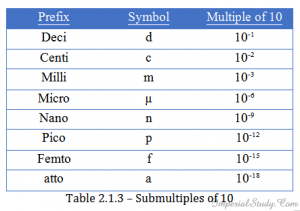

Submultiples:

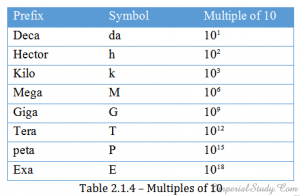

table1.3 Multiples :

table1.4 Some side-notes :

The following units of lengths are used for measuring very small units:

- 1 fermi/femtometre (fm) = 10-15 m

- 1 angstorm = 10-10 m

- 1 micron/micrometre = 10-6 m

The following units are used for measuring very large distances:

Light year : Distance travelled by light in vacuum in one year.

1 light year = 9.46 × 1015 m

Astronomical unit (AU) : Mean distance of the sun from the earth.

1 AU = 1.496 × 1011 m

Parallactic second (parsec) : Distance at which an arc of length one AU subtends an angle of one second of an arc.

1 parsec = 3.08 × 1016 m

Atomic mass unit:

In atomic and nuclear physics,, mass is measured in terms of atomic mass unit (a.m.u.).

One a.m.u. is defined as 1/12th of the mass of one Carbon-12 atom.

1 a.m.u. = 1.66 × 10-27 kg.

-

Science | Class 11th Notes | Physics | Unit- 1 Physical World And Measurements Chapter-1 Physical World

We provide students with the best science notes for class 11th that helps to repack the long and lengthy course into a short series of easy notes that reduces the burden from the shoulders of students regarding heavy course and hard study and shows them a new and easy way to study. Until class 10th, students were taught in a lengthy, easy and explained method so that their basic knowledge about science gets strong. Class 11th is about expanding that basic knowledge and have got a very lengthy course which is many times more than that of 9th and 10th class. Also, if a student seeks to go into competitions like I.I.T., A.I.E.E.E., A.I.M.M.S. than the load of study he needs to do is much more increased. This load can be decreased if he is presented his vast course in form of short and easy notes which the students can easily understand and learn. That is why we have prepared the whole large and vast course for Class 11th in form of short and easy notes for our students. You can read them and find it out for yourself how easy is to read and learn them. We would appreciate your feedbacks or suggestions in form of comments and if there is something still missing, we will be keeping updating the post for you. You must keep visiting the website to get those updates.

Science for class – XI

Unit -1: Physical world and measurements

Although we have been studying the physics from a long time, still there is not everything we have been able to clear out in our previous classes. We need to revisit the world of physics with a new dimension and explore the basics of physics and physical study again so that nothing remains uncovered and no single basic concept of physics is left. In unit Ist i.e. Physical world and measurements, we look at all the basic knowledge of physics so that armed with this knowledge we can move onto further deep study of physics in further units.

Chapter-1: Physical world

1.1 Introduction

We start this long journey of physics and physical world with a basic definition of physics and discuss about various branches of physics. We would discuss about some of the most inspiring physical discoveries and how they were made, forces operating in nature and some basic physical laws. Please note that the word physical means “related to physics”, so physical laws are laws related to physics, physical theories are theories related to physics and so on.

1.2 What is physics?

Physics- Physics is the study of nature. It is the branch of science dealing with the study of nature and natural phenomena.

Scientific theory- A scientific theory is a set-up that helps to explain a natural phenomenon or the behaviour of a natural system on the basis of the established laws of nature.

For example:- The theory of solar system, where sun occupies the central position is known as Copernican theory of solar system.

1.3 Physical theories and their branches

Today’s physics can be described and understood with the help of the following five theories:-

- Mechanics (or Newtonian mechanics) – The theory of motion of material objects at low speeds.

- Thermodynamics – The theory of heat, temperature and the behaviour of a system of a large number of particles.

- Electromagnetism – The theory of electricity, magnetism and electromagnetic radiation.

- Relativity- The theory of invariance in nature and the theory covering the motion of high-speed moving particles.

- Quantum mechanics – The theory of mechanical behaviour of sub-microscopic particles.

Note: Earlier, methods of measurements in in physics were of subjective nature i.e. these depended upon human senses of touch, hearing, sight etc.

- Methods of experiment in physics:

- Subjective methods – Methods of experimenting with the help of simple senses like hearing, seeing, touching, etc.

- Objective methods – Methods of experimenting with the help of scientific apparatus. It is used to reduce inaccuracies in subjective methods.

Why is physics called an ‘exact science’ ?

Because of the precision and accuracy in the measurement of physical quantities, physics is called an ‘exact science’ or the ‘science of measurements’.

1.4 How discoveries in physics are made ?

Physics is all about the nature and its phenomena. People observe nature and guess about how certain natural phenomena may happen. Experiments made by many scientists help to find out the reasons behind many natural phenomena. Scientist often find out big discoveries and new theories are made by them in various field of sciences. Some examples are:

Archimedes’ laws of floatation:- Archimedes was asked by a king to tell the purity of the gold in his crown without melting it. He got a clue to solve this problem while bathing in his tub and came out into the street shouting “Eureka! Eureka!” (“I have found it! I have found it!”). Thus he formulated the laws of floatation.

He found that a small drop of liquid is always spherical in shape. It never assumes cuboidal or any other geometric shape. Due to surface tension, liquids try to possess minimum surface area. It is because, for a given volume, the sphere has minimum surface area.

Electromagnetic induction:- When Faraday moved a magnet near a coil, a galvanometer connected to the coil showed deflection indicating the flow of current through it. This experiment led to Faraday’s theory of Electromagnetic induction.

Its study led to the design of electric generators, motors, etc.

Note:- The cause of forces like gravitational force, magnetic force, etc. is due to the exchange of particles between the two bodies, charges or magnetic poles. So, such forces are termed as Exchange Forces.

Rutherford’s experiment:- Rutherford’s experiment of scattering of α – particles by the gold foil led to the discovery of atomic nucleus. This experiment is also stated in Class 9th Chapter 4.

All the above stated experiments can be explained on the basis of a physical law and had led to important discoveries.

1.5 – Range of length, mass and time intervals in physics

Physical quantities like length, mass and time intervals (or simply time) vary over a wide range. This range can be observed as follows:

- Length: 10 -15 m (size of nucleus) to 1025 m (size of universe).

- Mass: 10 -30 kg (mass of an electron) to 1055 kg (mass of the universe).

- Time: 10-22 s (time taken by an electromagnetic radiation to cross a nuclear distance) to 1018 s (life of the sun).

We are able to make such wide ranging measurements with a few methods because:

- A quantitative study of the observations in nature tells that these can be explained and understood in terms of few laws.

- Though length, mass and time vary over a wide range, yet there is a fairly small number of principles which can be applied to measure them.

- The physical phenomena can be easily understood by separating more important features of a physical phenomenon from less important ones and the hidden complexities become clearer.

1.6 – Physics in relation to science

- Relation to maths – Physical theories make use of various mathematical concepts which help in the development of theoretical physics.

- Relation to chemistry – Study of structure of the atom, radioactivity, etc. have helped in rearrangement of elements in periodic table, to detect even traces of substances in a sample, to know the nature of valency, etc.

- Relation to biology – Optical microscope is helpful in the study of biology. Electron microscope has made it possible to see even the structure of cells. X-ray and neutron diffraction have helped in understanding the structure of nucleic acids. Radio-isotopes are used in radio therapy for curing skin diseases.

- Relation to astronomy – Modern telescopes help in the study of space and heavenly bodies. Quasars, pulsars have enabled the scientists to see into the farthest limits of the space.

1.7 – Forces in nature

There are four kinds of forces operative in nature:

- Gravitational force

- Weak force

- Electromagnetic force

- Nuclear (strong) force

We would first look at each of these forces in detail and then discuss their properties.

- Gravitational force – The force of attraction between two objects due to their masses is called gravitational force. The equation for gravitational force is, /r2

F = G M1 M2

/r2Where G (= 6.67 × 10 -11 N m2 kg-2) and is called Universal constant of gravitation.

2. Weak force – The force working between two leptons, a lepton and a meson or a lepton and a baryon. Leptons are class of elementary particles including electrons, muons, neutrinos and their antiparticles.

ß – decay- The ß – decay is an example of weak force interaction. In this process, a neutron inside a nucleus changes into a proton by emitting an electron and an uncharged particle, called antineutrino.

3. Electromagnetic force – The force of attraction or repulsion working between two electric charges in motion.

Also, if the charges are not moving, then the force is called the electrostatic force. The electrostatic force is the force between two static (non-moving) electric charges.

4. Nuclear force – The forces operating inside a nucleus between protons and neutrons. In general, the forces responsible for interaction between mesons, baryons and between mesons and baryons. Thus, it is due to interaction between nucleons (baryons) and π – mesons.

Properties:-

- Gravitational force:

- It obeys the inverse square law.

- It is always attractive in nature.

- It is a long range force i.e. it extends up to infinity.

- Its field particle is graviton.

- It is the weakest force operating in nature.

- It is a central and conservative force.

- Weak force:

- Weak forces are short range forces.

- The weak forces are about 1025 times stronger than the gravitational forces.

- In a weak interaction, neutrino acts as the field particle.

- Electromagnetic force:

- It obeys the inverse square law.

- It may be attractive or repulsive in nature.

- It is also a long range force.

- Its field particle is photon.

- It is about 1036 times stronger than gravitational force.

- It is also a central as well as conservative force.

- Nuclear force:-

- It varies inversely with some higher power of distance.

- It is basically an attractive force.

- It is a short range force and is operative only over the size of the nucleus.

- Its field particle is π – meson.

- It is the strongest force operating in nature, about 1038 times strongest than gravitational force.

- It is a non-central force.

1.8 – Physical laws of conservation

Finally, in this section, we will study about some conservative laws that are operative in nature. You may already have heard about these in previous classes:-

- Law of conservation of linear momentum: It states that if no external force acts on a system, the total linear momentum remains conserved. In absence of external force,

p1 + p2 = constant

Where p1 and p2 are linear momenta of the two bodies at any instant.

- It is obtained from Newton’s third law of motion.

- Follows the principle of homogeneity of space i.e. space possesses same properties at all the points.

Examples:

- When two billiard balls strike, they move in opposite directions.

- The recoil when a bullet is fired from a gun.

- Motion of the rockets.

- Law of conservation of energy: It states that energy can neither be created nor destroyed, but can change its form from one to another.

- It follows the work-energy theorem but can also be explained using principle of homogeneity of flow of timee. time flows uniformly.

- In mechanics, mass is considered fundamental to matter and matter acquires energy by virtue of its motion or configuration.

- Einstein’s mass-energy equivalent relation is E = m c2. This has led to law of conservation of mass and energy that unites both laws of conservation of mass and conservation of energy.

- Release of energy in nuclear fission and fusion is in accordance with this unified law.

Examples:

- The mechanical energy of a freely falling body remains constant. (Mechanical energy = Kinetic energy + Potential energy)

- On vibration, the mechanical energy of a simple pendulum remains constant while it swings between two extreme points.

- Law of conservation of angular momentum : It states that if no external torque acts on a system, the total angular momentum of the system remains conserved.

- It follows Newton’s third law of rotatory motion. Also, it can be obtained from principle of isotropy of space e. space possesses same properties in all directions.

Examples:

- Velocity of a planet orbiting the sun in an elliptical orbit increases when it is closer to the sun and decreases when it is far from the sun.

- The alarming high-speeds of inner layers of whirl-winds.

- A diver jumping from the spring board exhibits summersaults in air.

The other conservative laws are law of conservation of charge, spin, lepton number, baryon number, parity etc.

-

Science Class 9 Chapter – 8 : Motion | Notes | Study material and PDF download

Science for Class – IX (NCERT)

Chapter 8 – Motion

8.1- Introduction

Motion, as the word itself says, is the movement of different living and non-living things. We see birds flying, people moving, cars running – all of which are different types of motions that we come across in our everyday life. What can we study about motion? Why is the study of motion included in the study of physics? Let us go through this chapter to understand this.

8.2 – How do we describe motion?

How do we know that something is in motion or not? Before we discuss this topic furthermore, let us talk about two familiar terms that are necessary to know about in this chapter

Motion: The state in which an object (or person) is moving is called the state of motion.

Rest: The state in which an object (or person) is not moving is called the state of rest. So, for an object that is simply lying on the ground, we say that the object is in a state of rest.

Now coming back to the topic, how can we know that an object is moving? Or how can we say that and object is in the state of rest? If we find that the distance of an object from a fixed point is continuously increasing or decreasing, then we might say that the object is moving or the object is in the state of motion. The fixed point about which we are talking is also called the reference point or origin.

Origin: The origin is a reference point which is used to determine the state and location of an object. An object can be near, far, beside, below or above that reference point (or origin).

8.2.1- Motion along a straight line

To understand above points more clearly, we must learn about motion along a straight line. It is the simplest type of motion. To understand this concept more clearly, take the example of an object moving along a straight path.

Suppose, the object starts its journey from O, which is treated as its reference point or origin. Then A, B and C represent the position of that object at different intervals. Now, first the object moves towards A, passing the points C and B in its way. Then, it moves back along the same path and reaches at C passing through B.

Let us calculate the length that it has covered. It is OA + AC, i.e. 60 km + 35 km = 95 km. Here, in this case, we need to specify only the numerical value of the distance covered by the object in order to calculate it; we don’t need to specify the direction of motion. Many quantities are described by only their numerical value.

The numerical value of a physical quantity is also called its magnitude. Also, there are some terms that may appear many times in this and the next chapter:

Distance: The magnitude of length covered by an object is known as distance.

Initial position: Position of an object when it is at the origin or the position of an object before it has started to move is called its initial position. The word ‘initial’ means starting. So, initial position is the starting position of an object.

Final position: The position of an object after it has completed its movement/completed moving is called its final position. It is the position at which the object has stopped.

Displacement: It is the shortest distance between the initial position and the final position of an object. In this case, the displacement of the object is the distance between O and C i.e. 25 km.

Can the distance and displacement be equal?

The topic that we are going to discuss now is not about finding any relation between the distance and the displacement, but it focuses on the difference between the distance and the displacement.

Suppose, the object moves again from O to B. This time the distance is 35 km and the displacement is also 35 km. In such a simple case, the distance and displacement can be equal. Now, suppose the object moves from B to C. The distance in this case is 35 + 10 km (since B and C are at a distance of 10 km from each other)=45 km while the displacement would be 25 km which is the shortest distance between O and C. Also, suppose that the object returns back to O. The distance now would be 45 + 25 = 70 km. What is the displacement now?

We see that the initial position and the final position of the object are the same i.e. O. So, the displacement now would be zero. So, again the distance and displacement are not equal in this case. Thus we conclude that distance and displacement are two different quantities that are used to determine the overall motion of an object. We also conclude that the displacement can be zero in case the initial position and final position of an object coincide with each other (are at the same point).

8.2.2 – Uniform and Non-uniform motion

In this section, we discuss two categories of motion which are related to its speed, i.e. distance covered in unit time. Let us look at these terms:

Uniform motion: When an object covers equal amounts of distance in equal intervals of time, then it is called the uniform motion. For instance, suppose a man who is walking is able to walk 100 metres in one minute, another 100 metres in second minute and another 100 metres in the third minute, then it is the uniform motion.

Non-uniform motion: When an object covers unequal amounts of distance in equal intervals of time, it is called non-uniform type of motion. For instance, suppose when a car covers a distance of 30 km in one hour, 35 km in second hour and 32 km in third hour, then it is called the non-uniform motion.

8.3- Speed/Rate of motion

We know that different objects may take different amount of time in covering different amount of distance. Some may be slow and some may be fast. This rate at which an object covers the given distance is called its speed.

Also, we must introduce a familiar term, called the SI unit. Many of you may know about this term, but for those who don’t know, SI unit is a unit in which a given quantity can be expressed. To understand this more clearly, look at the table of SI units of familiar quantities that is given below:

We see that distance is usually expressed in metres, so its SI unit is ‘Metre’ or ‘m’ in short. Again, the displacement is nothing but another type of distance, so its SI unit is again ‘Metre’ or ‘m’. In the case of time, its basic unit is second so its SI unit is also ‘Second’ or ‘s’ in short.

Now, speed is also a quantity. So, there is an SI unit of speed too. The SI unit of speed is metre per second or m/s. This is also referred as m s-1. There are some other units of speed like centimetre per second (cm s-1), and kilometre per hour (km h-1). These are not the SI units but these units are commonly used while specifying the speed of an object.

Average speed: The total amount of distance travelled by an object in the total amount of time is known as the average speed of that object. We use average speed because speed of most objects is non-uniform and keeps changing.

Average speed =

Total distance travelled / Total time taken

So, if an object travels a distance s in time t, the speed v is,

v=s/t

For example, suppose a car travels a distance of 120 km in 3 hrs, then its average speed v is 120/3 = 40 km/h. The car might not have travelled at 40 km/h at all the time and sometimes it may have been faster or slower, but this is the average speed of the car.

8.3.1- Speed with direction

When we specify the direction of motion along with its speed, we are referring to its velocity. Velocity is the speed of an object moving in a specific/definite direction. The velocity of an object can be either uniform or variable. The velocity can be changed by changing object’s speed, changing object’s direction of motion or changing both speed and direction of motion.

Average velocity:

If an object is moving along a straight path, we can express the magnitude of its rate of motion in terms of its average velocity.

Suppose the velocity of an object is changing at a uniform rate, then the average velocity can be given by finding the arithmetic mean of the initial velocity and the final velocity for a given period of time.

Average velocity =

(Initial velocity + Final velocity)/2

Mathematically, vav =

(u + v)/2

Where vav is the average velocity, u is the initial velocity and v is the final velocity of the object. SI unit of velocity is the same as that of speed i.e. m/s or m s-1.

For example, suppose the initial velocity of an object is 200 km/h and final velocity is 250 km/h then the average velocity is 200 + 250/2 = 450/2 which is equal to 225 km/h.

8.4- Acceleration

As we have discussed earlier, the velocity of an object does not remain the same all time but keeps changing, i.e. the velocity is not uniform all the time. In case of uniform velocity, there is no change in the velocity, which means that the change in the velocity of the object is ‘zero’. In case of non-uniform motion, velocity keeps changing with time. It has different values at different intervals of time. So, in case of non-uniform motion, the change in velocity is not zero.

Acceleration:

There is another quantity called acceleration, which is used to measure the rate of change of velocity of an object per unit time. We can define acceleration as:

Acceleration =

Change in velocity/Time taken

Now, suppose the velocity of an object changes from initial velocity u to the final velocity v in the time t, the acceleration a is:

a = (v-u)/t

Accelerated motion: Motion in which the velocity of an object keeps changing or is non- uniform is called the accelerated motion.

If the acceleration is in the direction of the velocity, then it is taken as positive. If the acceleration is in the opposite direction of velocity, then it is taken to be negative. The SI unit of acceleration is m/s2 or m s-2. There are two types of acceleration:

- Uniform acceleration: If an object travels in a straight line and its velocity increases or decreases by equal amounts in equal intervals of time, then it is the uniform acceleration. Take the example of a freely falling object, which is moving in uniform acceleration.

- Non-uniform motion: If the velocity of an object increases or decreases by unequal amounts in equal intervals of time, then it is the non-uniform motion. Take the example of a car moving along a straight road increasing its speed by unequal amounts in equal intervals of time, then the car is moving with non-uniform acceleration.

8.5- Graphical Representation of Motion

Now, when we have talked about various concepts regarding motion, we must also discuss about representing motion with the help of graphs. Graphs make it easy to present basic information and one can learn more easily with the help of graphs. So, to describe the motion of an object, we can use line graphs. These graphs are discussed below:

8.5.1- Distance-Time Graphs

Distance – Time graphs can be used to represent the change position of an object with time by using a convenient scale of your choice. In such graphs, time is taken along the x-axis and distance is taken along the y-axis. Distance time graphs can be used to show conditions of uniform motion, non-uniform motion, or when the object is at rest, etc.

Graph for uniform speed-

When an object travels equal distance in equal intervals of time, it is moving with a uniform speed. In such case the distance travelled by the object is directly proportional to the time taken. Thus for uniform speed, the distance-time graph would be a straight line.

The distance-time graph can be used to determine the speed of an object. We just need to measure the distance between two points on the given line using the y-axis and measure the time using x-axis. Then the speed v is equal to,

v = (s2-s1) / (t2-t1)

Image source: Google images

Graph for non-uniform speed-

The distance-time graph for non-uniform speed is different from that of uniform motion as it is in the form of a curve. This graph shows the non-linear variation of the distance travelled by an object with time.

Image source: Google images

8.5.2- Velocity-Time Graphs

In velocity-time graphs, the time is taken along the x-axis and the velocity is taken along the y-axis. Now, let us discuss about velocity-time graphs for uniform and non-uniform velocity:

Graph for uniform velocity-

In case of uniform velocity, the height of the velocity-time graph will not change with time. It will be a straight line parallel to the x-axis.

Image source: Google images

The product of the velocity and time gives the displacement of an object which is moving with a uniform velocity. So, in our graph, the area enclosed by the velocity-time graph and the time axis will be equal to the magnitude of displacement. In above graph, the distance moved by the object in time (t2-t1) is equal to AC ×CD;

= [(40 km/h) × (t2-t1) h]

= 40 (t2-t1) km

= area of rectangle ABCD which is shaded in blue colour

Graph for uniformly accelerated motion-

Before moving to non-uniform motion, it is important to discuss about the velocity-time graph for a uniformly accelerated motion of an object. In such cases, for example when a car is moving with uniformly accelerated velocity, the velocity changes by equal amounts in equal intervals of time. So, in every case of uniformly accelerated motion, the velocity-time graph is a straight line.

In the following graph, we can determine the distance travelled by the object by calculating the area of figure ABCDE under the velocity-time graph that is given below.

i.e. the distance, s = area ABCDE

= area of rectangle ABCD + area of triangle ADE

Image source: Google images

= [AB × BC] + [½(AD × DE)]

Graph for non-uniform velocity-

For non-uniform velocity, there is not much thing to look at except to see how these graphs do look. There are two types of such graphs available:

- Motion of an object whose velocity is decreasing with time

Image source: Google images

As you can see, there is not much thing to discuss about this graph as this graph is self-explanatory.

2. Non-uniform variation of velocity of an object with time

Image source: Google images

However, in the above graph you can see that the non-uniform motion has been represented by zigzag lines which is divided into several parts. You can easily find out the magnitude of distance by calculating Area of ( triangle AOG + rectangle ABFG + trapezium BCEF + triangle CDE ).

8.6 – Equations of Motion using the Graphical Method

When an object is moving along a straight line with uniform acceleration, then its velocity, acceleration during the motion and the distance covered by it in a certain time interval can be related with the help of certain equations which are known as the equations of motion. These equations are:

v = u + at —- (i)

s = ut + ½ at2 —- (ii)

2 a s = v2 – u2 —- (iii)

where,

u – initial velocity v – final velocity

a – uniform acceleration s – distance travelled

t – time taken

These three equations can be represented using the graph which is given below:

Image source: Google images

8.6.1- Equation for Velocity-Time Relation

In the graph given above, consider a body moving with a uniform acceleration a, with the initial velocity u and the final velocity v in the time t. The perpendicular lines BC and BE are drawn from B to x-axis and y-axis. The initial velocity is OA and final velocity is BC. Also, the time taken is OC. AD || OC.

Now,

BC = BD + DC

= BD + OA

Substituting BC = v and OA = u,

v = BD + u

Or, BD = v – u

Acceleration = Change in velocity/Time

a = BD/AD = BD/OC

Or, a = (v – u)/t

v – u = at

Or, v = u + at

8.6.2- Equation for Position-Time Relation

Now, again in the same graph we can take the distance s as:

s = area of OABC (which is a trapezium)

= OA × OC + ½ (AD × BD)

Now, substituting OA = u, OC = AO = t

BD = v – u = at

s = u × t + 1/2 (AD × BD)

s = ut + ½ (t × at)

or, s = ut + ½ at2

8.6.3- Equation for Position-Velocity Relation

Again in the same graph, we have,

s = area of trapezium OABC

= (OA +BC) × OC/2

Substituting OA = u, BC = v and OC = t,

s = (u+v) t/2

From velocity-time relation,

t = (v-u)/a

s = (v+u) × (v-u)/2a

Or, 2as = v2– u2

8.7- Uniform Circular Motion

Now we have come to the last topic of our first physics chapter of class 9th i.e. uniform circular motion. Since there are a lot of questions asked about this topic in exams, we must discuss this whole chapter little by little breaking it into various subtopics. Let us first start with the definition of this term itself:

Uniform Circular Motion:

The motion in a circular path with uniform speed is known as uniform circular motion. Thus, an object moving in a circular path with uniform speed is said to be moving in uniform circular motion.

Now let us move to further discussions:

Changing of directions during circular motion:

Suppose an object moves on a rectangular path, then the object has to change its direction four times before it completes its path. Similarly, in a hexagon, it will change its direction six times and in a octagon, it will change its direction eight times. If we go on increasing the number of sides indefinitely, the shape of the path would slowly approach the shape of a circle and the length of the sides would be decreased into a point. Also, an object that is moving along a circular path would change its direction an indefinite number of times as the number of sides is increased by an indefinite number.

Change of velocity during circular motion:

When an object moves along a circular path, the only change in its velocity is due to the change in the direction of motion. Thus, the motion of an object moving along a circular path is also an example of accelerated motion.

Calculating the velocity during motion on a circular path:

Suppose the radius of the circular path is r, then its circumference is given by 2πr. If an object takes t seconds to go once around the circular path, the velocity v is given by

v = 2πr/2

Example of uniform circular motion:

If you take a piece of thread and tie a small piece of stone at one of its ends, then hold the other end of the thread in one hand and move the thread in a circular motion, it will be an example of an object moving in uniform circular motion. If, at any instance, you release the thread from your hand, the thread would move in a straight line which shows that the direction of motion changed at every point when the stone was moving along the circular path.

Other examples of uniform circular motion are the movement of moon and the earth, a satellite in a circular orbit around the earth, a cyclist on a circular track at constant speed and an athlete rotating his body before throwing a hammer or discuss.

So, here our first physics chapter of Motion for class 9th comes to an end. We have discussed all important topics and you need to be clear in all these topics because these are simply the basic topics and would be useful in higher studies as the higher studies are all based on these small topics that you learn in the small classes. If you have any other doubt, leave a comment or contact us using our e-mails provided in our site or go to [email protected] .

-

Is Matter Around Us Pure Science Chapter 2 | Notes, Study Materials & PDF Download

Science for class-IX (NCERT)

Chapter 2: Is Matter Around Us Pure

2.1- Introduction

In the previous chapter, we learned about matter. In this chapter, we would discuss about mixtures, compounds, and elements. We would learn about different types of mixtures and discuss what matter is pure or not pure.

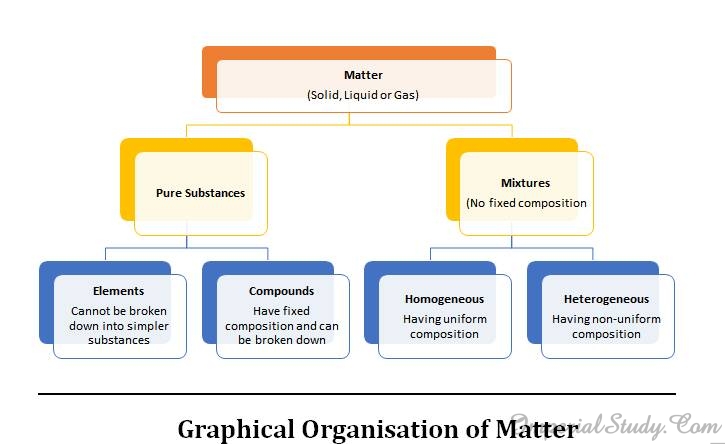

2.2- Mixture

When two or more pure forms of matter combine together, it is known as a mixture. These pure forms of matter are also known as substance.

Substance:-Any form of matter that cannot be separated into other kinds of matter by using any physical means is known as substance. For e.g.- sodium chloride or salt is a substance and cannot be separated into other forms by any means. Another example is water or H2O.

Some examples of mixture can be:

- Soft Drinks that are prepared by mixing various ingredients, flavors, and colors together.

- Cement is a mixture of limestone, silica and some other material.

- Air around us is itself a mixture of various gases like Oxygen, Nitrogen, Carbon Dioxide etc.

2.3- Types of mixture

Depending upon the nature of the constituents of the mixture, a mixture can be categorized into three types:

2.3.1- Solution

The homogenous mixture of two or more substances is called a solution. In a solution, all the particles of the constituents are evenly distributed within the mixture. The components of a solution are the solvent and the solute. Some examples of solutions are:

- Alloys, which are the mixtures of two or more metals or a metal and a non-metal that cannot be separated into their components by physical methods. Brass is an alloy containing 30% zinc and 70% copper.

- As discussed above, air is also a homogenous mixture of various gases that are uniformly mixed together in fixed percentage.

Also we have used words solvent and solute above, which we can define as follows:

Solvent:- The component of the solution that dissolves the other component in it is called solvent. Generally, it is the component present in a larger amount.

Solute:– The component of the solution that dissolves within the solvent is called solute. Generally, it is the substance present in a smaller amount.

Keeping above points in mind, we can find some more examples regarding a solution:

- A mixture of sugar in the water is an example of solid mixed inside a liquid solution. In this solution, water acts like the solvent and sugar act like solute.

- ‘Tincture of iodine’, which is a solution of iodine in alcohol, contains iodine as the solute and alcohol as the solvent.

- The aerated drinks like soda water, cola drinks, are solutions of gas inside liquid. They contain carbon dioxide as the solute and water as solvent.

- The air around us is a solution of gas inside gas. It contains gases like 21% Oxygen and 78% Nitrogen as the main components and numerous other gases that are present in a very small percentage.

Properties of a solution:-

- A solution is a homogeneous mixture.

- The particles of a solution are smaller than 1 nm (10-9 metre) and cannot be seen with naked eyes.

- Because of such small particles size, they do not scatter a beam of light passing through the solution. So, the path of light is not visible in a solution.

- The solute particles can’t be separated from the mixture using filtration. The solute particles do not settle down in a solution, so a solution is stable.

Concentration of a solution:-

Concentration refers to the amount of solute present in the solution in a given solution mixture. It is the amount of solute present per unit volume or per unit mass of the solution/solvent. There are three types of concentrations for a solution:

- Dilute solution: When the amount of solute present in the solution/solvent is low, then it is a dilute solution.

- Concentrated solution: When the amount of solute present in the solution/solvent is high, then it is a concentrated solution.

- Saturated solution: When the amount of solute present in the solution/solvent is equal to the full capacity (i.e. the solution has dissolved as much solute as it can hold) of the solution, then it is called a saturated solution. Also, if the amount of solute contained in a solution is less than the saturation level, it is called an unsaturated solution.

Solubility:-The maximum amount of solute which a solution can hold at the given temperature, or in other words, the maximum capacity of a solution for holding the solute particles at a given temperature is called the solubility of that solution.

Concentration of a solution=Amount of solute/Amount of solution

Or

Amount of solute/Amount of solvent

2.3.2- Suspension

A suspension is a non-homogeneous mixture in which the solid particles are dispersed in the liquid. In other words, a suspension is a heterogeneous mixture in which the solute particles do not dissolve but remain suspended throughout the bulk of the medium. The particles of a suspension can be seen with naked eyes. Some examples of a suspension are given below:

- A mixture of sand in water. The sand particles are insoluble and remain suspended.

- Muddy water is also a suspension of mud in water.

Properties of a suspension:-

- A suspension is a heterogeneous mixture.

- Particles of a suspension are visible to the naked eyes.

- Particles of a suspension can scatter a beam of light passing through them and make its path visible.

- Solute particles can settle down when left undisturbed and then, can be separated by the process of filtration. In other words, a suspension is an unstable mixture.

Note:When the particles of a suspension settle down, the suspension breaks and it does not scatter light anymore. This explains more clearly that why we call a suspension unstable.

2.3.3- Colloid or Colloidal solution

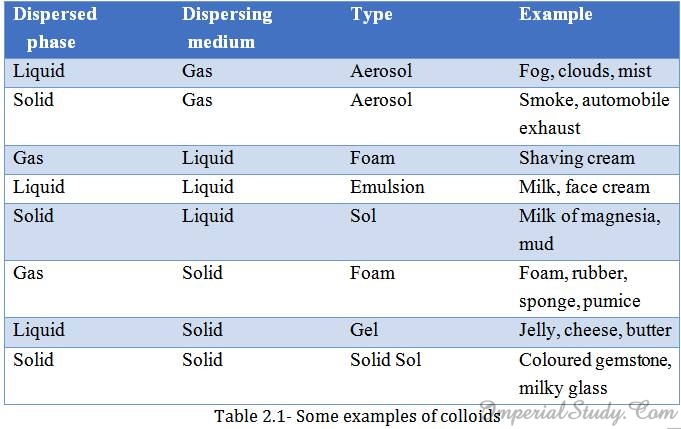

A colloidal solution or colloid is a heterogeneous mixture, in which the particles are uniformly spread in the solution. The particles are too small to be seen with naked eyes, but large enough to scatter a beam of light. Colloids are used in industries and also in daily life. There are two components of a colloid:

- Dispersed phase:The particles that are uniformly spread throughout the solution are called the dispersed phase.

- Dispersion medium: The medium in which the particles are spread is called the dispersion medium.

Before we talk more about colloidal solutions, let’s discuss about an important scientific phenomenon which we have been mentioning above:

Tyndall effect:-It is the phenomenon in which a beam of light gets scattered or in other words, the scattering of a beam of light is called the Tyndall effect. It was named after the scientist who had discovered it.

So, when we say that a suspension or colloidal solution can scatter a beam of light, we mean that a suspension or colloidal solution shows Tyndall effect.

This effect can also be observed when a small beam of light enters a room through a small hole. This is due to the scattering of light by the particles of dust and smoke in the air. It can also be observed when sunlight passes through the canopy of a dense forest. This is due to the mist, containing tiny droplets of water, which act as particles of colloid dispersed in air.

Properties of a colloid:-

- A colloid is a heterogeneous mixture.

- Particles of a colloid are too small to be seen with naked eyes.

- Particles of colloid are big enough to scatter a beam of light passing through it and make its path visible.

- Particles of a colloid do not settle down when left undisturbed, or in other words, a colloid is quite stable.

- Particles of a colloid cannot be separated from the mixture by filtration. However, a special technique called centrifugationcan be used to separate them.

Note:Colloids are classified according to the state i.e. solid, liquid and gas, of the dispersing medium and the dispersed phase. In the following table given below, you can see some examples of colloids that we come across in our daily life:

2.4- Techniques used to separate the components of a mixture

The particles of heterogeneous mixtures can be easily separated by easy methods like sieving, handpicking and filtration. However, apart from these simple techniques, there are some special techniques that can be used to separate the components of mixture. In this section, we will discuss about some of these techniques with examples.

2.4.1- Evaporation

Evaporation is a separation technique used to separate a volatile component from its non-volatile solute. This method can be used to separate coloured component (dye) from blue/black ink. Ink is a mixture of dye in water. We can observe this technique with the help of the following activity:

- Take a beaker and fill it half with water.

- Now put a watch glass on the mouth of the beaker.

- Put a few drops of ink on the watch glass.

- Start heating the beaker. Observe the evaporation taking place from the watch glass.

- Keep heating until any further change cannot be observed

- You will see that the Dye has been separated from the blue/black ink.

2.4.2- Centrifugation

We have already talked about centrifugation earlier. Now we must discuss what centrifugation is and where it is used. This technique works on the principle that the denser particles are forced to the bottom and lighter particles stay at the top when spun rapidly. For this purpose, a centrifugation machine is used. (While sometimes a milk churner can also be used when the technique is used on full cream, toned or double-toned milk) Here is a small activity to understand centrifugation:

- Take some full-cream milk in a test tube.

- Use a centrifuging machine (or a milk churner) for two minutes.

- You can see that the cream has been separated from the milk.

Applications/Uses of Centrifugation:-

- It is used in the diagnostic laboratories for carrying out blood and urine tests.

- It is commonly used in dairies or at home to separate butter/cream from milk.

- It is used in washing machines to squeeze out the water from dirty clothes.

2.4.3- Separation of immiscible liquids

Immiscible liquids are liquids which cannot be mixed together. The technique used to separate two immiscible liquids is quite simple and we can observe it with the help of a small activity in which we try to separate kerosene oil from water using a separating funnel:

- Take the mixture of kerosene oil and water.

- Pour the mixture in a separating funnel.

- Let it undisturbed for some time until separate layers of oil and water are formed.

- Open the stopcock of the separating funnel and pour out the lower layer of water carefully.

- Now, close the stopcock as the oil reaches it.

- Kerosene oil and water have been separated.

Applications/Uses of using a separating funnel (or a similar tool):-

- This technique is used to separate the mixture of oil and water.

- This technique is used in the extraction of iron from its ore. For this purpose, the lighter slag is removed from the top to leave the molten iron at the bottom in the furnace.

This technique works on the principle that immiscible liquids separate out in layers depending on their densities.

2.4.4- Sublimation

Sublimation is a technique used to separate mixtures that contain a sublimable volatile component from a non-sublimable impurity. Please note that in the first chapter we have learnt that sublimation is the process of changing of state directly from solid into a gas. This process is thus also used in separation techniques. Some solids that sublime are ammonium chloride, camphor, naphthalene and anthracene. Below is a small activity to show separation of ammonium chloride and salt mixture by sublimation:

- Take a china dish and put some mixture of ammonium chloride and salt on it.

- Take a funnel and put it inverted over the china dish.

- Now put a cotton plug in the mouth of the inverted funnel.

- Start heating the china dish. Vapours of ammonium chloride would be formed inside the apparatus and solidified ammonium chloride would be deposited on the walls of the funnel.

- Keep heating until there are no more vapours.

- Remove the funnel. You would find that the salt is left behind on the china dish.

2.4.5- Chromatography

The name of this technique has been derived from the word ‘Kroma’ of Greek language which means ‘Colour’. This is due to the fact that this technique was first used in the separation of colours.

Chromatography is the technique that is used to separate those solutes which dissolve in the same solvent. Below is an activity to show how to separate different colours from black ink using chromatography:

- Take a thin strip of filter paper.

- Take a pencil and draw a line on the filter paper. This line should be approximately 3 cm above the lower edge.

- At the centre of the line, put a small drop of ink from a sketch pen or fountain pen. Let this ink dry.

- Take a test tube (or a glass, beaker, jar, etc) containing water and lower the filter paper into it in such a way that the drop of ink is just above the water level. Leave it undisturbed.

- As the water rises up, you would observe different colours on the filter paper strip i.e. different colours have been separated from black ink.

Note:In the above activity, the ink has water as the solvent and the black ink/dye as the solute. As the water level rises, the filter paper takes along the dye particles with it. A dye is generally a mixture of two or more colours. So, the colour that is more soluble in water rises faster and the colours get separated from the black ink/dye.

Applications/Uses of Chromatography:-

- It is used to separate colours from a dye.

- It is used to separate pigments from natural colours.

- It is used to separate drugs from blood.

2.4.6-Distillation

In the above sections, we have discussed about separating two immiscible liquids. In this section we will discuss about a special technique called distillation that is used to separate two miscible liquids.

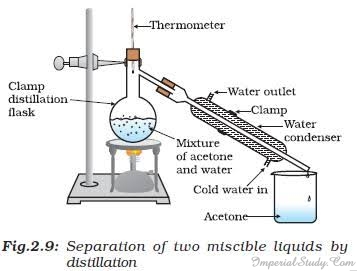

Distillation is used for the separation of components of a mixture containing two miscible liquids which boil without decomposition and have sufficient difference in their boiling points. Below is a small activity that shows how to separate a mixture of acetone and water with the help of distillation:

- Take the mixture of acetone and water.

- Pour it in a distillation flask and fit it with a thermometer.

- Attach the flask with a clamp and a water condenser on one side.

- Put a jar/beaker at the outlet of the water condenser.

- Heat the mixture slowly, closely watching the thermometer.

- Observe that the acetone vaporizes, condenses in the condenser and can be collected from the outlet into the jar/beaker.

- Observe how the water is left behind in the distillation flask.

Source: NCERT Fractional Distillation:-

We have discussed the distillation process above. However, there is another related process called fractional distillationwhich we would discuss in this same section.

Fractional distillation is the process used to separate a mixture of two or more miscible liquids for which the difference in their boiling points is less than 25 K. Some applications of this process are the separation of different gases from the airand separation of different factions from petroleum products. The apparatus used in this process is similar to that of a simple distillation, except for that a fractionating column is fitted in between the distillation flask and the condenser.

Fractionating column:It is a tube packed with glass beads. The glass beads provide surface area for the vapours to cool and condense repeatedly.

2.4.7- Separation of different components of air

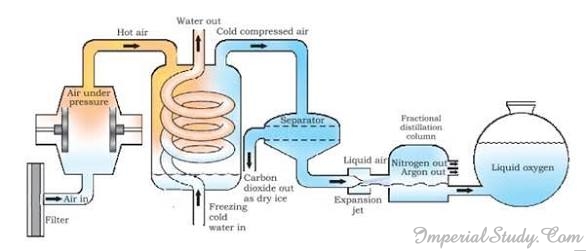

We have already discussed before that the air is a mixture of various gases like oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, helium etc. Is there a way to separate these gases from the air? The answer is- fractional distillation. In the previous section, we mentioned fractional distillation. In this section, we will discuss that how this technique is used in the separation of various gases from the air around us.

Suppose we want a specific gas, say oxygen, out of the air mixture, then we simply need to separate out all the other gases present in the air. This process can be understood by the help of following steps:

- Firstly, the air is compressed by increasing the pressure.

- Then, it is cooled by decreasing the temperature and liquid air is obtained.

- The liquid air is allowed to warm up slowly in a fractional distillation column.

- The different gases in air get separated at different heights depending upon their boiling points.

The first gas that gets separated is Carbon dioxide that separates out as dry ice after the cold compressed air reaches the ‘separator’. Next gas that separates is nitrogen followed by argon that separate in the fractional distillation column. Oxygen in the form of liquid (liquid oxygen) is left behind and thus we separate oxygen from the mixture of air.

Source: NCERT 2.4.8- Crystallisation

The last technique that we will discuss in this section is crystallisation. Crystallisation is a process that separates a pure solid from a solution in the form of its crystals. This method is used to purify solids. For instance, the salt we obtain from seawater is not pure and can have lots of impurities within it. For such impurities, we use the crystallisation process. We can understand this process with a simple activity:

- Take about 5 g of impure sample of copper sulphate (CUSO4) in a china dish.

- Dissolve it in the least amount of water.

- Filter out the impurities using filtration.

- Now evaporate the water from the copper sulphate solution so that you get a saturated solution.

- Now cover this solution with a filter paper.

- Leave it undisturbed for a day at room temperature so that it cools down.

- After a day, you will obtain the crystals of copper sulphate in the china dish.

Now another question that arises is that which process is better? The similar evaporation process or the crystallisation process? The answer is crystallisation. Why?

Why the crystallisation method is better than evaporation:-

Although there may be many reasons to elaborate the answer, below are two main reasons to answer this question that has arisen:

- Evaporation is not a better technique because some solids may get decomposed and even some solids like sugar may get charred/burned on heating to dryness.

- Evaporation is not a better technique because some impurities may remain dissolved in the solution even after filtration and on evaporating, these impurities may contaminate the solid.

Applications/Uses of Crystallisation:-

- Crystallisation is used in the purification of salt that we obtain from seawater.

- It is also used in the separation of crystals of alum (phitkari) from impure samples.

So, these are the few techniques that are used in the separation of the components of mixture depending upon the nature of the components of the mixture. Now, it is time to discuss about an important concept which have already studied in previous classes and see how this concept is useful to understand this chapter.

2.5- Physical and Chemical changes

So as we have discussed in the previous chapter, the concept is necessary to understand the difference between a pure substance and a mixture. Let us understand this concept with the help of few terms:

- Physical properties:The properties of a substance that can be observed and specified are called physical properties. For example- colour, hardness, rigidity, fluidity, density, melting point, boiling point, etc. are all physical properties.

- Physical change:A change in the physical property of any solid, liquid or gas is called a physical change. So, change in colour, change in shape, change in state are all physical changes.

The interconversion of states (or change of state) is also a physical change because it has no effect on the chemical composition or chemical nature of that substance.

- Chemical properties: The properties of a substance that determine its chemical nature and chemical composition, like how the substance would react with fire, how does the substance smells, what is the chemical composed of, etc. are all the chemical properties of that substance.

- Chemical change: A change in the chemical composition or chemical properties of a substance is called a chemical change. An important characteristic of chemical change is that new substances are formed in a chemical change. A chemical change is also called a chemical reaction. You would study more about chemical reactions in Class 10th,

Burning of candle:During the burning of a candle, both physical and chemical changes take place. The wax is melted, which is a physical change while the carbon dioxide gas that is evolved is a chemical change in the wax.

2.6-Types of Pure substances

Now when we have already discussed a lot about mixtures of different substances, it is finally the time to discuss about pure substances and their types. This concept is really necessary to understand as you would be learning more about them in upcoming chapters as well as in higher classes.

On the basis of their chemical composition, we can classify the substances as elements and compounds. Let us discuss about them in detail:

2.6.1- Elements

An element is a basic form of matter that cannot be broken down into simpler substances by using chemical reactions. This definition of an element has been given by a French chemist, Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743-94). Furthermore, Robert Boyle was the first scientistthat first used the term element in 1661. Elements are generally divided into metals, non-metals and metalloids.

Metals and their properties:-Metals are hard, shiny substances that generally show some or all of these properties:

- They have a lustre (shine).

- They have silvery-grey or golden-yellow colour.

- They conduct heat and electricity.

- They can be drawn into wires i.e. they are ductile.

- They can be hammered into thin sheets i.e. they are

- They make a ringing sound when they are hit i.e. they are

Some metals are iron, zinc, copper, gold, silver, sodium, potassium, etc. Mercury is the only metal that is liquid at room temperature.

Non –metals and their properties:- Non-metals are soft, non-conductors of heat and electricity that show some or all of these properties:

- They are available in a variety of colours.

- They are poor conductors of heat and electricity.

- They are neither lustrous, sonorous, malleable or ductile.

Some non-metals are hydrogen, iodine, carbon, bromine, chlorine, etc.

Metalloids: The elements that have intermediate properties between metals and non-metals, i.e. some properties of metals and some properties of non-metals are called metalloids. Some metalloids are boron, silicon and germanium.

Now coming back to elements, here are some important facts about elements that you must look at:

- There are more than 100 elements known today out of which ninety-two are naturally occurring while the rest are man-made.

- Most of the elements known at present are solid.

- Eleven elements are in gaseous state at room temperature.

- Two elements are liquid at room temperature i.e. mercury and bromine.

- The elements Gallium and Cesium become liquid at a temperature slightly above the room temperature. (303 K)

2.6.2- Compounds

A compound is a substance which is composed of two or more elements which are chemically combined with one another in a fixed proportion or a fixed amount. Examples of compounds are sulphur chloride, hydrogen sulphide, ammonium sulphate, and even water. You can easily conclude that in a compound, say sulphur chloride, the elements sulphur and chlorine are combined in fixed proportions

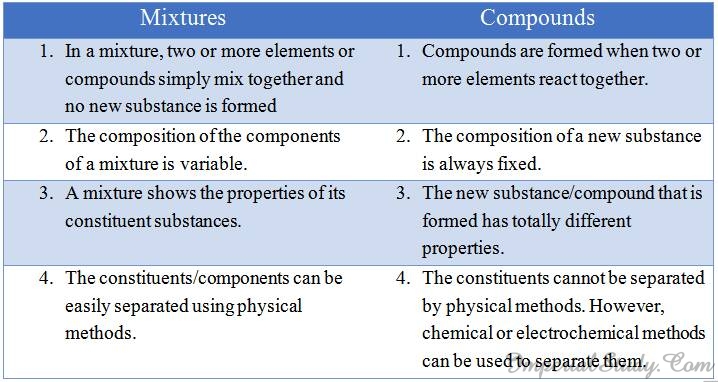

Difference between mixtures and compounds:-

Look at the following table in order to understand the difference between mixtures and compounds:

ORES

ORES