CBSE Class-12 Chemistry

Quick Revision Notes

Chapter 16

- Drugs: Drugs are low molecular mass substances which interact with targets in the

body and produce a biological response. - Medicines: Medicines are chemicals that are useful in diagnosis, prevention and

treatment of diseases - Therapeutic effect: Desirable or beneficial effect of a drug like treatment of

symptoms and cure of a disease on a living body is known as therapeutic effect - Enzymes: Proteins which perform the role of biological catalysts in the body are

called enzymes - Functions of enzymes:

- The first function of an enzyme is to hold the substrate for a chemical reaction.

Active sites of enzymes hold the substrate molecule in a suitable position, so that it

can be attacked by the reagent effectively. - The second function of an enzyme is to provide functional groups that will attack

the substrate and carry out chemical reaction.

- Role of drugs: Main role of drugs is to either increase or decrease role of enzyme

catalysed reactions. Inhibition of enzymes is a common role of drug action. - Enzyme inhibitor: Enzyme inhibitor is drug which inhibits catalytic activity of

enzymes or blocks the binding site of the enzyme and eventually prevents the binding

of substrate with enzyme. - Drug can inhibit attachment of substrate on active site of enzymes in following ways:

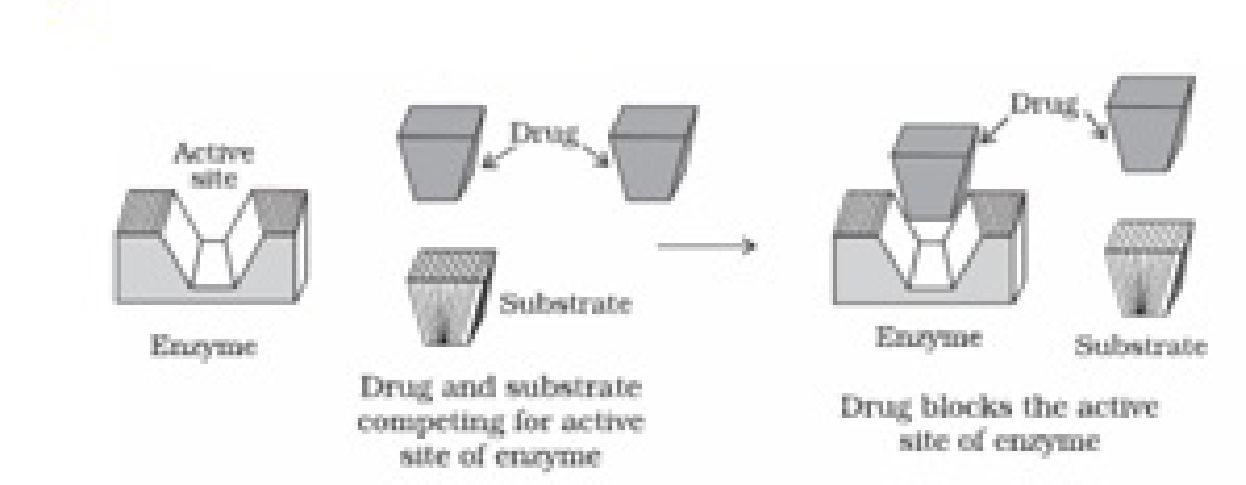

- Competitive Inhibition: Competitive Inhibitors are the drugs that compete with the

natural substrate for their attachment on the active sites of enzymes.

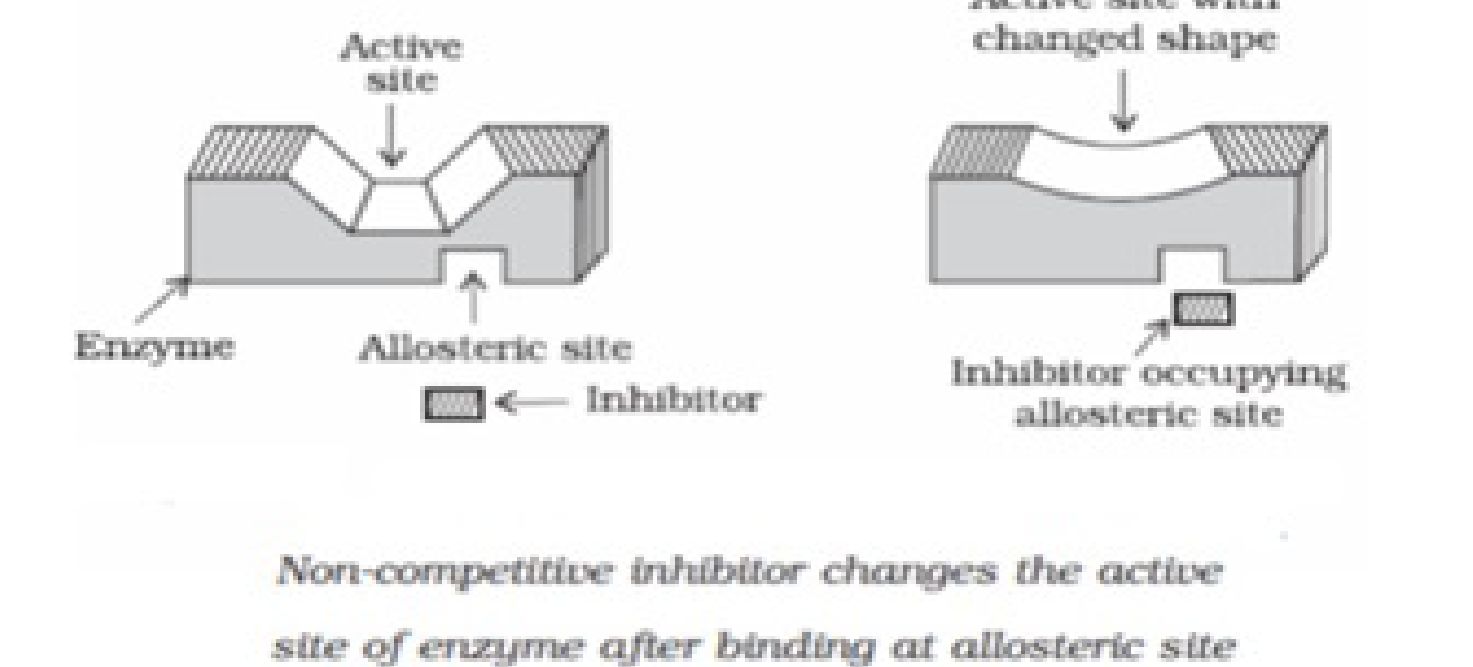

- Non-Competitive Inhibition: Some drugs do not bind to the enzyme’s active site, instead

bind to a different site of enzyme called allosteric site. This binding of inhibitor at

allosteric site changes the shape of the active site in such a way that substrate cannot

recognise it. If the bond formed between an enzyme and an inhibitor is a strong covalent

bond and cannot be broken easily, then the enzyme is blocked permanently. The body

then degrades the enzyme-inhibitor complex and synthesizes the new enzyme.

Ar I 1 ■ ■ r■ blli> ur| I fl

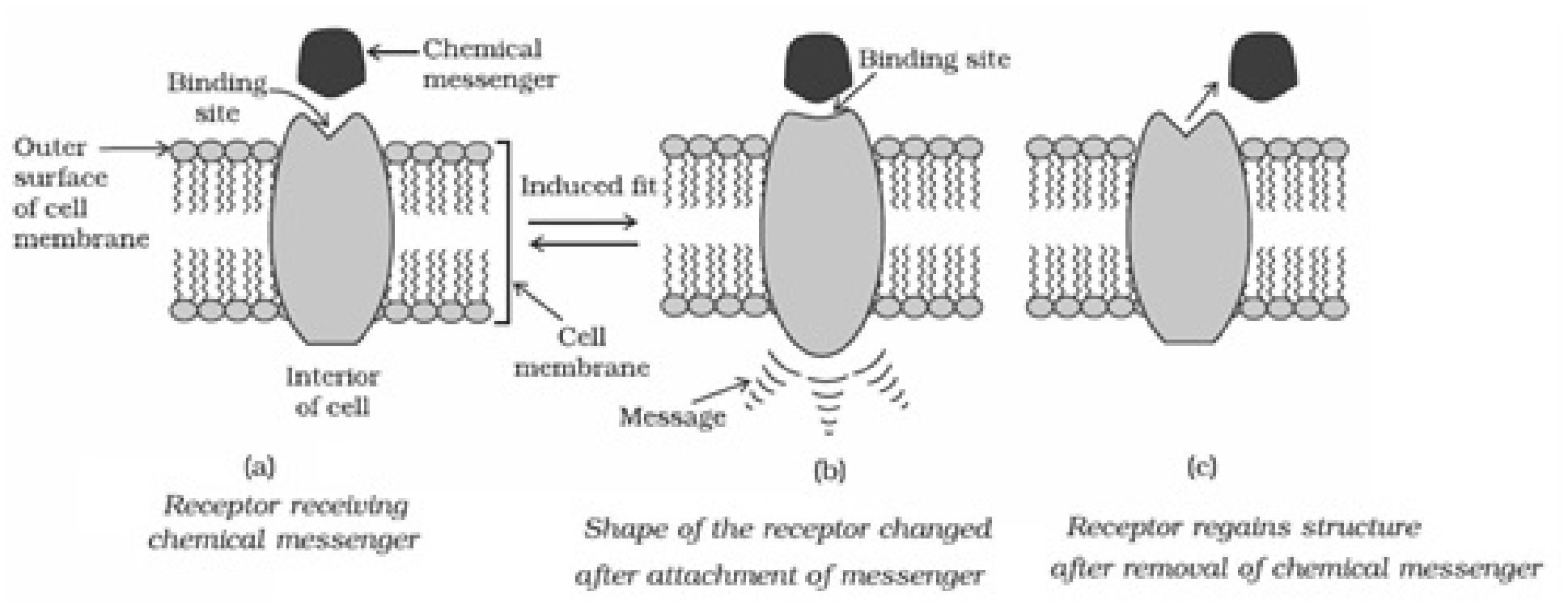

- Receptors: Proteins which are vital for communication system in the body are called

receptors. Receptors show selectivity for one chemical messenger over the other

because their binding sites have different shape, structure and amino acid

composition.

- Receptors as Drug Targets: In the body, message between two neurons and that

between neurons to muscles is communicated through chemical messengers. They

are received at the binding sites of receptor proteins. To accommodate a messenger,

shape of the receptor site changes which brings about the transfer of message into the

cell. Chemical messenger gives message to the cell without entering the cell.

- Antagonists and Agonists: Drugs that bind to the receptor site and inhibit its natural

function are called antagonists. These are useful when blocking of message is

required. Drugs that mimic the natural messenger by switching on the receptor are

called agonists. These are useful when there is lack of natural chemical messenger. - Therapeutic action of different classes of drugs:

- Antacid: Chemical substances which neutralize excess acid in the gastric juices and

give relief from acid indigestion, acidity, heart burns and gastric ulcers. Examples:

Eno, gelusil, digene etc. - Antihistamines: Chemical substances which diminish or abolish the effects of

histamine released in body and hence prevent allergic reactions. Examples:

Brompheniramine (Dimetapp) and terfenadine (Seldane). - Neurologically Active Drugs: Drugs which have a neurological effect i.e. affects

the message transfer mechanism from nerve to receptor.

- Tranquilizers: Chemical substances used for the treatment of stress and mild or

severe mental diseases. Examples: Derivatives of barbituric acids like veronal, amytal,

nembutal, luminal, seconal. - Analgesics: Chemical substances used to relieve pain without causing any

disturbances in the nervous system like impairment of consciousness, mental

confusion, in coordination or paralysis etc. - Classification of Analgesics:

- Non-narcotic analgesics: They are non-addictive drugs. Examples: Aspirin,

Ibuprofen, Naproxen, Dichlofenac Sodium. - Narcotic analgesics: When administered in medicinal doses, these drugs relieve

pain and produce sleep. Examples: Morphine and its derivatives - Anti-microbials: Drugs that tends to destroy/prevent development or inhibit the

pathogenic action of microbes such as bacteria (antibacterial drugs), fungi (anti-

fungal agents), virus (antiviral agents), or other parasites (anti-parasitic drugs)

selectively. - Anti-fertility Drugs: Chemical substances used to prevent conception or fertilization

are called anti-fertility drugs. Examples – Norethindrone, ethynylestradiol (novestrol).

- Antibiotics: Chemical substances produced by microorganisms that kill or prevent

the growth of other microbes.

Classification of antimicrobial drugs based on the mode of control of microbial

diseases:

- Bactericidal drugs – Drugs that kills organisms in body. Examples – Penicillin,

Aminoglycosides, Ofloxacin. - Bacteriostatic drugs – Drugs that inhibits growth of organisms. Examples – Erythromycin,

Tetracycline, Chloramphenicol.

Classification of antimicrobial drugs based on its spectrum of action:

- Broad spectrum antibiotics – Antibiotics which kill or inhibit a wide range of Gram-

positive and Gram-negative bacteria are called broad spectrum antibiotics. Examples –

Ampicillin and Amoxycillin. - Narrow spectrum antibiotics – Antibiotics which are effective mainly against Gram-

positive or Gram-negative bacteria are called narrow spectrum antibiotics. Examples-

Penicillin G. - Limited spectrum antibiotics -Antibiotics effective against a single organism or disease

- Antiseptics: Chemical substances that kill or prevent growth of microorganisms and can

be applied on living tissues such as cuts, wounds etc., are called anti-spetics. Examples –

Soframicine, dettoletc. - Disinfectants: Chemical substances that kill microorganisms but cannot be applied on

living tissues such as cuts, wounds etc., are called disinfectants. Examples – Chlorine (Cl2),

bithional, iodoform etc.

- Food additives: Food additives are the substances added to food to preserve its flavor

or improve its taste and appearance. - Different types of food additives:

- Artificial Sweetening Agents: Chemical compounds which gives sweetening effect to the

food and enhance its flavour. Examples – Aspartame, Sucrolose and Alitame. - Food preservatives: Chemical substances which are added to food material to prevent

their spoilage due to microbial growth. Examples – Sugar, Salts, Sodium benzoate - Food colours: Substances added to food to increase the acceptability and attractiveness of

the food product. Examples – Allura Red AC, Tartrazine - Nutritional supplements: Substances added to food to improve the nutritional value.

Examples -Vitamins, minerals etc. - Fat emulsifiers and stabilizing agents: Substances added to food products to give texture

and desired consistency. Examples – Egg yolk (where the main emulsifying chemical is

Lecithin) - Antioxidants :Substances added to food to prevent oxidation of food materials. Examples

– ButylatedHydroxy Toluene (BHT), ButylatedHydroxy Anisole (BHA).

- Soaps: It is a sodium or potassium salts of long chain fatty acids like stearic, oleic and

palmitic acid.

CH2^H

!

o

CH2– O-C-C17H3s

I O

M

CH – O – C – C17Hjs + 3NaOH

I O

J A [1 * .,

CH2– O-C-C17Hjs

Glyceryl ester Sodium

of stearic acid (Fat) hydroxide

» 3CiyHJSCOONa + CH -OH

I

(Soap) CH1^H

Sodium Gtycerol

stearate

This reaction is known as saponification.

- Types of soaps:

- Toilet soaps are prepared by using better grades of fats and oil sand care is taken to

remove excess alkali. Colour and perfumes are added to make these more attractive. - Transparent soaps are made by dissolving the soap in ethanol and then evaporating the

excess solvent. - In medicated soaps, substances of medicinal value are added. Insome soaps, deodorants

are added. - Shaving soaps contain glycerol to prevent rapid drying. A gum called, rosin is added

while making them.It forms sodium rosinate which lathers well. - Laundry soaps contain fillers like sodium rosinate, sodium silicate, borax and sodium

carbonate. - Soaps that float in water are made by beating tiny air bubbles before their hardening.

- Soap chips are made by running a thin sheet of melted soap ontoa cool cylinder and

scraping off the soaps in small broken pieces.

- Soap granules are dried miniature soap bubbles.

- Soap powders and scouring soaps contain some soap, a scouring agent (abrasive) such as

powderedpumice or finely divided sand, and builders like sodium carbonate and

trisodium phosphate.

- Advantages of using soaps: Soap is a good cleansing agent and is 100%

biodegradable i.e., micro- organisms present in sewage water can completely oxidize

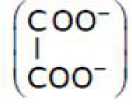

soap. Therefore, soaps do not cause any pollution problems. - Disadvantages of using soaps: Soaps cannot be used in hard water because hard

water contains metal ions like Ca2+ and Mg2+ which react with soap to form white

precipitate of calcium and magnesium salts

2C17HyCOONa-CaCl- ^ % NaCl– Ca

^oap ftGoltfbte Cd L. Lur.

::=:^i:r (ioap)

2C-H3jCOOXa+MgCl3 ^2 NaCl-(C-H3jCOO)3Mg

iQap ir.E■:■ It’Dh ™ zr.dE i.um

E-[ddfd te (EC-Erp)

These precipitates stick to the fibres of the cloth as gummy mass and block the ability of

soaps to remove oil and grease from fabrics. Therefore, it interferes with the cleansing

ability of the soap and makes the cleansing process difficult.

In acidic medium, the acid present in solution precipitate the insoluble free fatty acids which

adhere to the fabrics and hence block the ability of soaps to remove oil and grease from the

fabrics. Hence soaps cannot be used in acidic medium

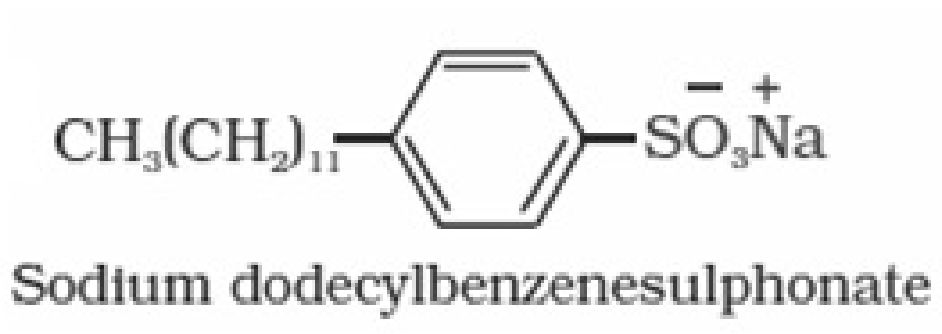

• Detergents: Detergents are sodium salts of long chain of alkyl benzene sulphonic

acids or sodium salts of long chain of alkyl hydrogen sulphates.

• Classification of detergents:

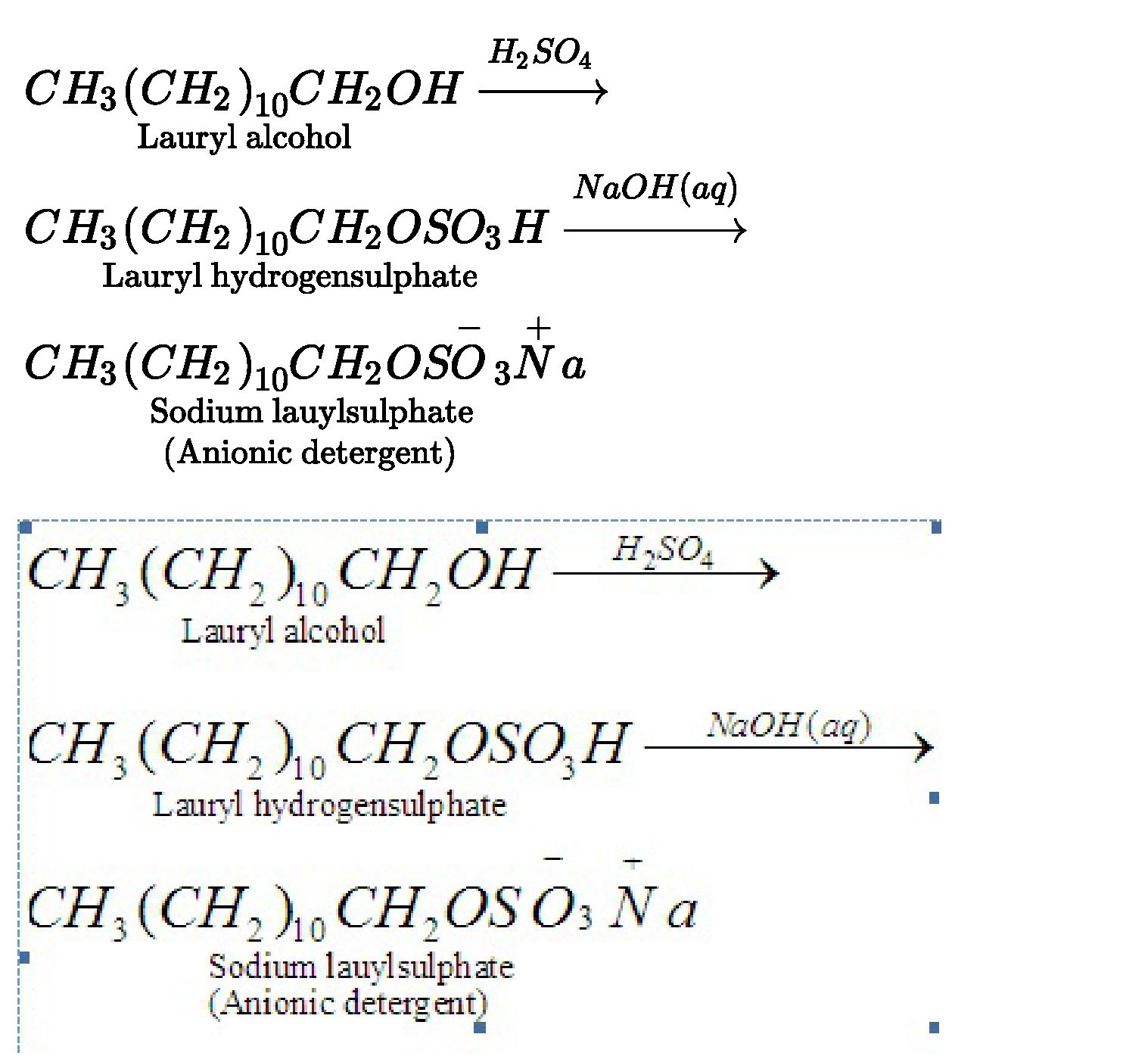

- Anionic detergents: Anionic detergents are sodium salts of sulphonated long chain

alcohols or hydrocarbons. Alkyl hydrogen sulphates formed by treating long chain alcohols

with concentrated sulphuric acid are neutralised with alkali to form anionic detergents.

Similarly alkyl benzene sulphonates are obtained by neutralising alkyl benzene sulphonic

acids with alkali. Anionic detergents are termed so because a large part of molecule is an

anion.

They are used in household cleaning like dishwasher liquids, laundry liquid detergents,

laundry powdered detergents etc. They are effective in slightly acidic solutions where soaps

do not work efficiently.

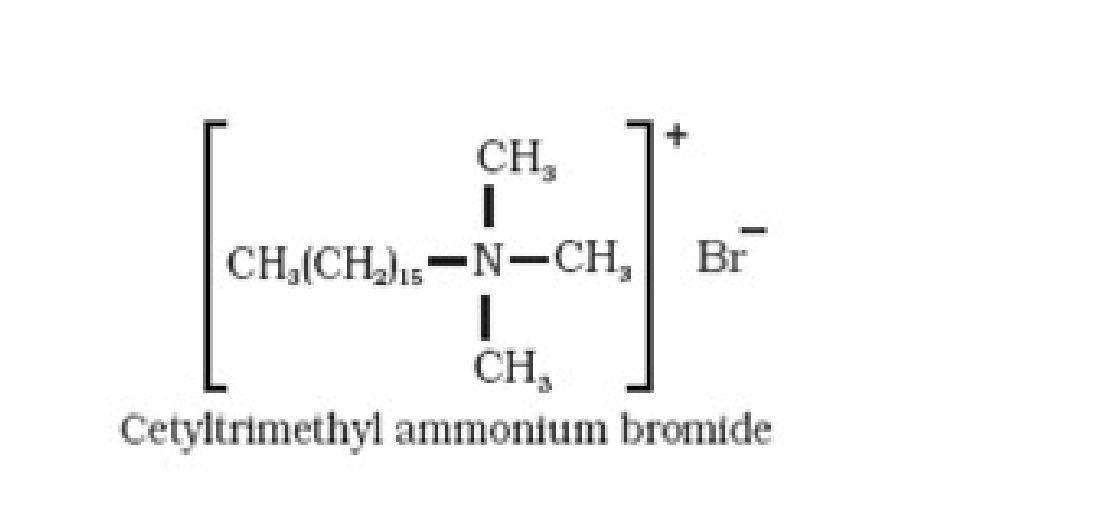

- Cationic detergents: Cationic detergents are quarternary ammonium salts of a mines with

acetates, chlorides or bromides as anions. Cationic parts possess a long hydrocarbon chain

and a positive charge on nitrogen atom. Cationic detergents are termed so because a large

part of molecule is a cation. Since they possess germicidal properties, they are used as

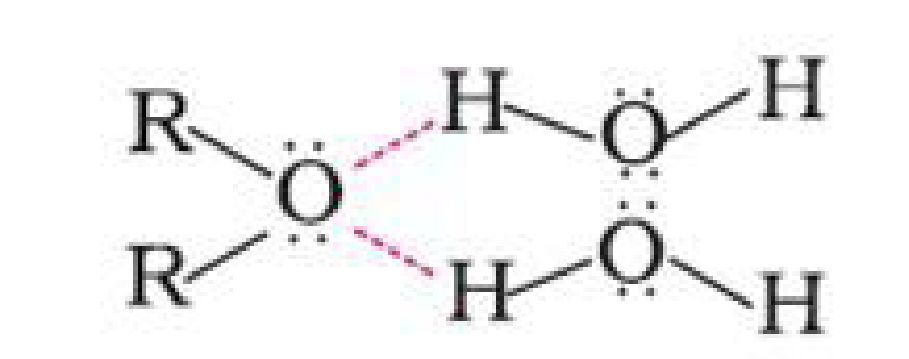

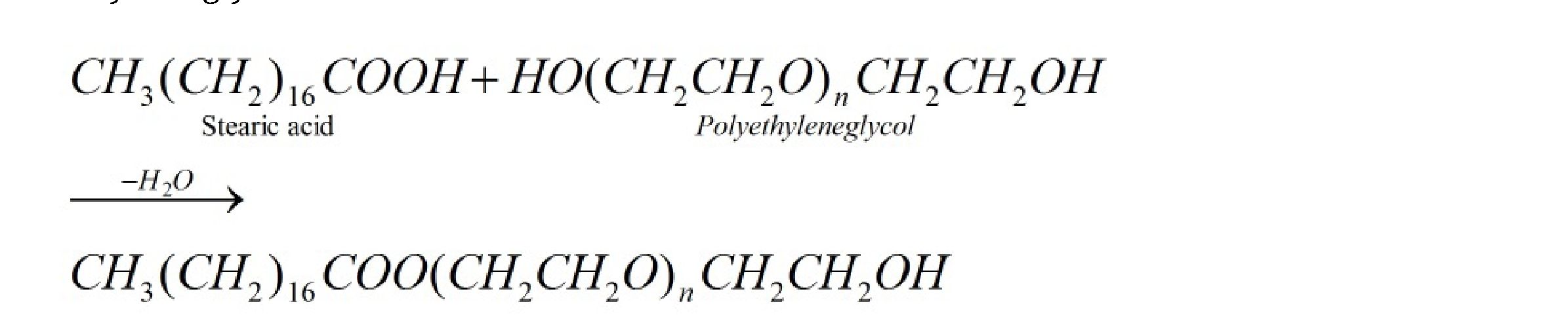

germicides. They has strong germicidal action, but are expensive. - Non- ionic detergents: They do not contain any ion in their constitution. They are like

esters of high molecular mass.

Example: Detergent formed by condensation reaction between stearic acid reacts and poly

ethyl eneglycol.

It is used in Making liquid washing detergents. They have effective H- bonding groups at one

end of the alkyl chain which make them freely water soluble.

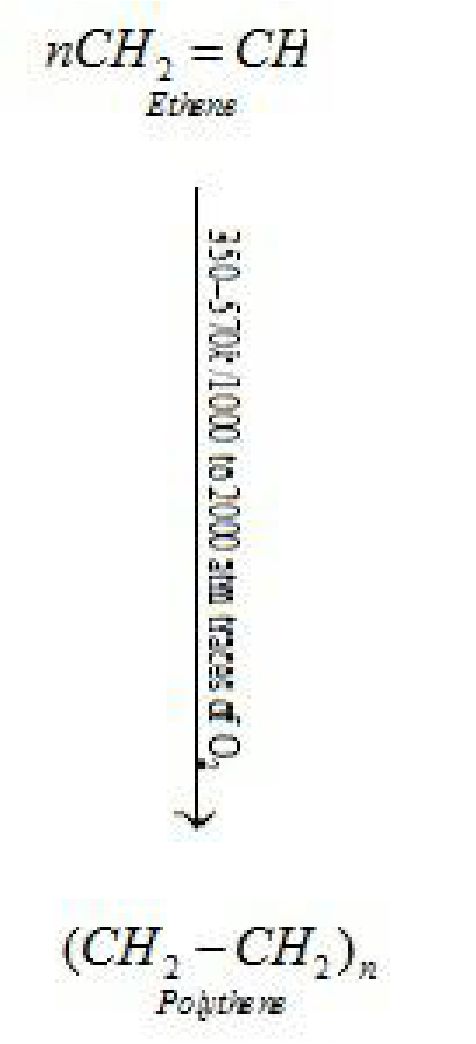

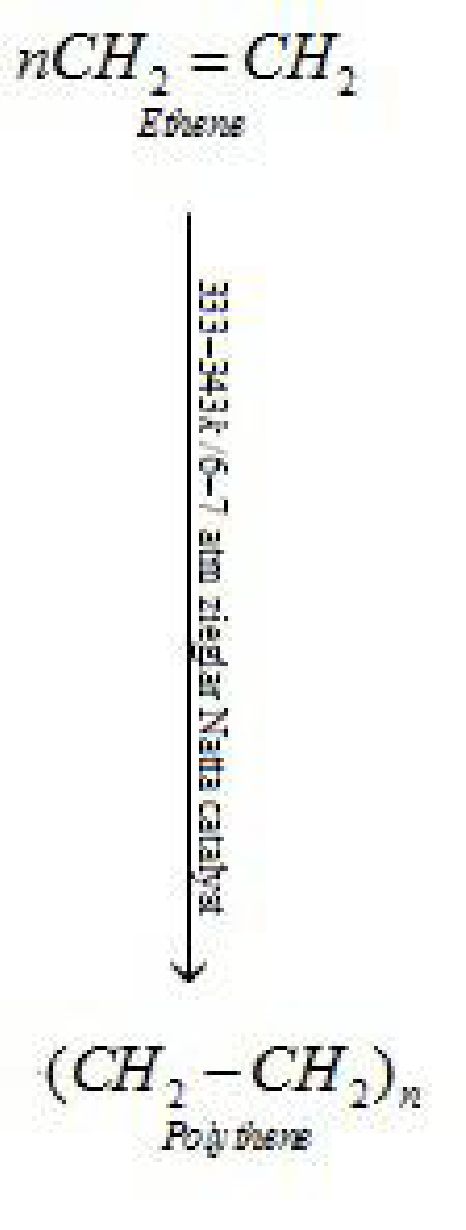

- Biodegradable detergents: Detergents having straight hydrocarbon chains that are

easily decomposed by microorganisms. Example: Sodium lauryl sulphate

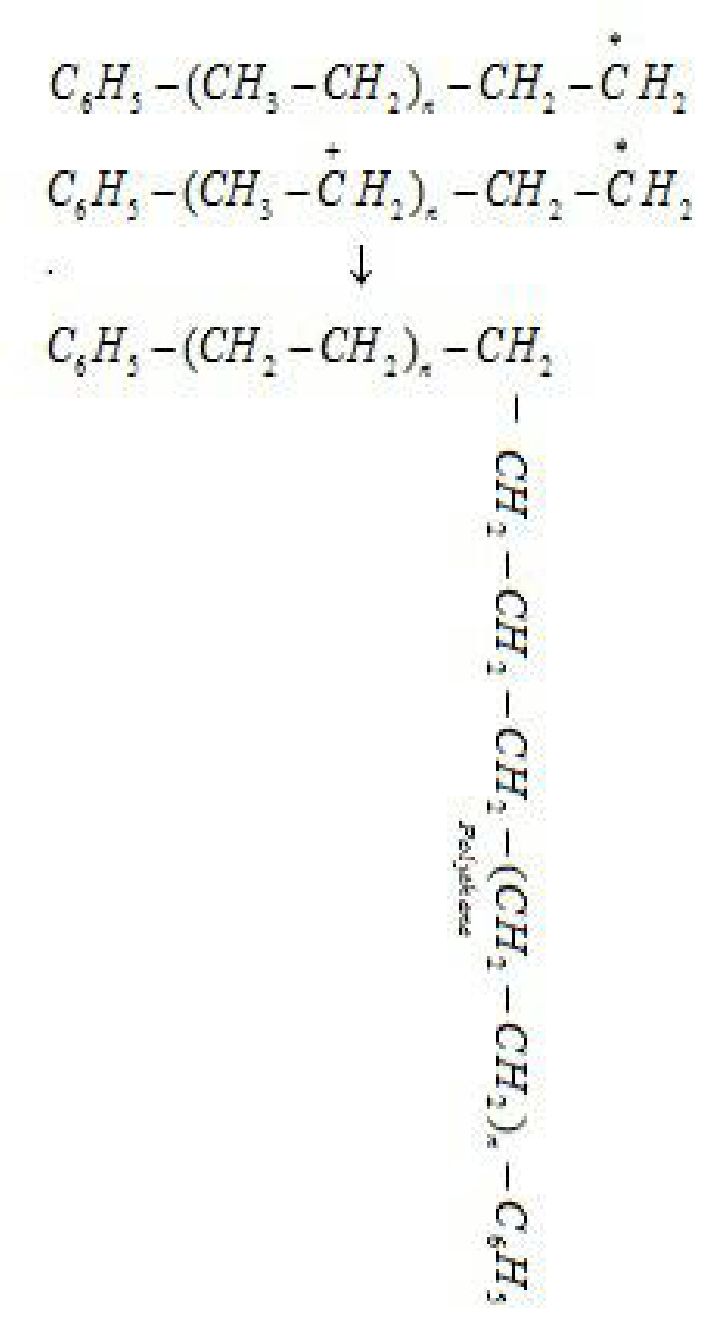

- Non-Biodegradable detergents: Detergents having branched hydrocarbon chains

that are not easily decomposed by microorganisms.